By Lawrence Pearce

The Uncanny (noun): In Freudian psychology, the psychological phenomenon of something being strangely familiar, but not just merely mysterious or surreal; a sense of psycho-emotional familiarity has to be present.

Trainspotting (verb): 1.) Watching trains and writing down the numbers on the railway engines. 2.) Trying to read the label on a vinyl record that the DJ is spinning at the club whilst looking over their shoulder.

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

Chapter One: The Uncanny Valley

Do you remember those weird, completely CGI family movies made in the first part of the 21st century where all the human characters were animated in the computer? Little pea-sized sensors were placed all over a performer (usually a real movie star like Tom Hanks or Alec Baldwin or some ultra Americana person like that) and a whole new artificial character was constructed around the actor through the industrial light and magic of software.

Millions of innocent pixels lost their lives to create these eerie, completely creepy, totally fake looking “people”: 3D cadavers that weren’t nearly as sexy as mannequins, and not nearly as seductive as hand drawn cartoons. Something about the way the eyes looked really bothered us, a waxy, corpse-y, re-animated lifelessness stared back at us with Tom Hank’s voice and Jim Carrey’s body… or worse, and even weirder, Alec Baldwin’s voice with Ben Affleck’s face.

This eeriness, this morbid oddness that never ever looked “real” and never had any of the soul or charm of Pixar’s purposeful cartoonishness (Tom Hanks as Woody is way more alive than Tom Hanks as Mustache Train Station Guy in Polar Express) became known as “The Uncanny Valley,” a term borrowed from a much earlier term used in artificial intelligence research to describe the phenomenon by which human perception of an almost human looking A.I. leads to a deep rooted abjection in the observer. The artificial subject is almost nearly real, but because it just misses the mark, people despise the artificial subject more than they would if it was just a tad more fake and artificial looking.

Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (2001)

The Orson Welles of this digital flesh parade was Robert Zemekis, Spielberg’s flashiest disciple of gee whiz, Reagan Era mass escapism, directing such multiplex classics as Back to the Future about a teenager who travels back to the 50s, Who Framed Roger Rabbit? about classic cartoon characters inhabiting the real world alongside real humans, and later Forrest Gump (Newt Gingrich’s favorite movie) about a simpleton who happens to be present during many of Post-War America’s historical moments thanks to the magic of CGI: all films which, like Stranger Things, play with American values and manipulate people’s expectations and their insatiable appetite for manufactured Nostalgia.

Watching the first few episodes of The Duffer Brother’s “new” show Stranger Things on Netflix is like staring into the heart of darkness of The Uncanny Valley even though none of the characters are generated with software (except for the prerequisite creature on the loose), and none of the characters are animatronic robots. All the humans “are humans.” It’s a weird experience at first. In the first few minutes of the very first episode alone, there are so many S/Os, references, and appropriations to a former era’s science fiction/horror cinematic past that I felt drunk.

We’ve been here before. We’ve even been here before that. We’ve seen that logo “somewhere.” We’ve seen those kids facing a supernatural mystery that’s both dangerous and filled with wonder somewhere too. An extremely peculiar deja vu doesn't so much as creep in as you watch Stranger Things as it rushes over you like a sudden poltergeist kicking down the door of the closet, throwing toys and books around your bedroom. I was initially revolted, like seeing one of those nightmarish hospital robots from Japan whose videos flooded our Facebook newsfeeds a few years ago, but also weirdly fascinated. I kept watching.

Stranger Things (2016)

Chapter Two: Not Spielberg

In the fall of 1983, a scientist runs down a dark corridor of some underground complex only to be attacked in the elevator from above by something mysterious and possibly supernatural in origin. Cut to four twelve year olds playing a furious game of Dungeons & Dragons. Pizza’s involved. The older sister in her room upstairs is on the phone talking to a boy way longer than she probably should be. The kids zoom home after their game in the night on their BMX bikes, their mounted flashlights beaming through the dark. One kid, Will Byers, goes his own way home by himself. Mistake. There’s a humanoid shape in pursuit. Will gets inside. Calls for help. He drops the phone. Close up of the dangling phone. Will runs to the shed and locks it. Will gets “abducted.” Cut to the next morning. Will’s friends are confronted by the school bullies (they aways travel in pairs… always: bullies and toadies.)

There’s a distraught mother played by Winona Ryder (because I guess Drew Barrymore wasn’t available?), a goodhearted, but troubled sheriff who’s turned to the bottle, Will’s older brother, Jonathan Byers, the perfect Stephen King young male archetype/stereotype (more on him later), and a mysterious girl with a shaved head, cursed with telekinetic powers with an unknown past named Eleven (incidentally, the word “eleven” is “elf” in German.) And so, The Duffer Brother’s saga set in the early 80s but made in 2016 begins…

We’ve just seen a blatant, if effective, mashup of key elements from three of Spielberg’s most iconic films in the first ten minutes of an eight hour Netflix binge series: Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, and Poltergeist (note: though Tobe Hooper is credited with directing Poltergeist, it's widely known and accepted today that Steven Spielberg directed the majority, if not the entirety, of the film.)

What’s going on here? And why by the third episode can’t I stop watching? Why do I give a crap about any of these kids? Why am I interested in whether Will Byers is still alive or not?

The answer, surprisingly, after watching it all the way through, is the show, despite the hype that this is all one big Amblin karaoke jamboree, though it is undoubtedly indebted to the 80s video store classics and Stephen King books which The Duffer Brothers want you to know loud and clear (they really LOVE The 80s, and they wear their influences on their sleeves as brightly as E.T.’s orange glowing heart), isn't really “Spielbergian” in style except in a very surface way when you begin to look a little closer. Stranger Things may evoke Spielberg in a general way with the kids, their D&D, their bikes, flashlights blasting through the mist, and the spooky humanoid silhouettes in the foggy night air, but the Spielberg influence stops there.

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

Technically speaking, upon closer examination, the way any given scene unfolds on the show isn't Spielbergian, nor the manner in which the camera is set up in any shot. I kept thinking of the 90s while watching Stranger Things. Those dark, droney synth patches swooning over the soundtrack and those ominous establishing shots of a house or building surrounded by leafless trees at perpetual dusk are from Twin Peaks, not Spielberg, as are those moody interiors smothered in yellow and brown light. The clandestine government project and all those tense interrogations are straight out of The X-Files or Silence of the Lambs, not Close Encounters.

Akira (1988)

The music in the show is ambient, pensive, and subtle, not operatic or emotionally didactic and emphatic like in a Spielberg movie. John Williams’ Spielberg stuff makes us boohoo even when when we’re listening to it on its own. Stranger Things’ music is moody and haunting, oscillating between the eerie textures inspired by Aphex Twin’s brilliant Selected Ambient Works Vol. II and Cliff Martinez’s moody “doo-nee-doo-nee-doo-nee” minimal arpeggiating: the polar opposite of John Williams. It’s not very John Carpenter-ish either, really. The only stylistic similarity Michael Stein and Kyle Dixon’s Stranger Things score shares with Carpenter’s stuff is that they're both generated with electronic instruments. Stranger Things’ music score is its own thing. There’s no part in the show where I thought “that sounds just like a John Carpenter piece.” It’s fresh and different in spite of the cacophony of namedropping you may’ve heard on The Internet.

The character of Eleven is a nicer version of Tetsuo from Akira, not one of Spielberg’s lonely tweens. She’s the outsider archetype of the story, the fish out of water trope, the “E.T.” who’s unfamiliar with the world she’s stumbled into, mesmerized by television, and creeped out by makeup. In fact, none of the kids seem all that lonely in the typical Spielberg tween angst sort of way. They all seem like tight friends and siblings despite the occasional bickering and one of the kids being very skeptical of Eleven and her role in the gang at crucial point in the story. But their already tight bond only strengthens as the adventure unfolds. Spielberg’s kids, particularly in E.T. and Poltergeist, have a sadness to them from being torn apart by divorce or supernatural forces. They seem lost and broken. Though there is a broken family in Stranger Things, the family seems functional, not dysfunctional, better off being away from the dickhead dad.

The younger kids in Stranger Things felt more to me like the lovable dorks from Freaks & Geeks (which also took place in the early 80s) than Elliot and his brother and sister in E.T. or the raunchy, annoying loudmouths in The Goonies. If anything, the show’s a paranormal Freaks & Geeks (though it’s not a comedy.) The only genuine loner on the show is Will Byers’ older brother, Jonathan.

Freeks and Geeks (1999)

Chapter Three: Loners and Libraries

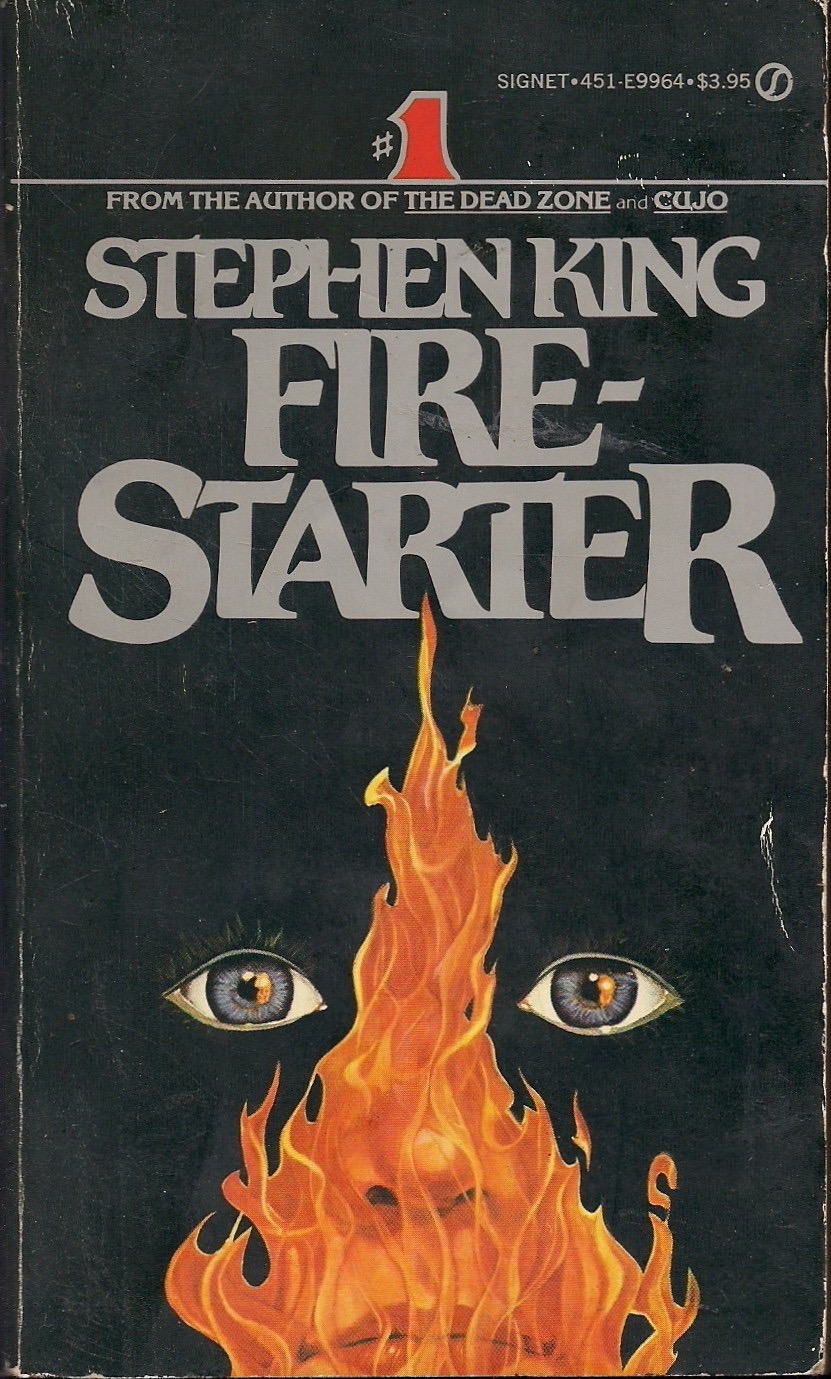

Stephen King’s influence and inspiration over Stranger Things looms the largest of all. More than Spielberg, more than The X-Files, more than anything else. Stylistically and thematically, it not only owes everything to the actual books of King, but more to all those R-rated quasi Spielbergy Stephen King film adaptations like Firestarter, Christine, Cat’s Eye, and Silver Bullet that filled Cinemax’s late night schedule for years and years, as well as those uncountable made for TV event miniseries based on some Stephen King book that wasn't ever as good as the books, but we watched anyway because Netflix hadn’t been invented yet. They usually started on a Sunday night, and finished a few days later on another school night. I usually had to record them because of that terrible thing called bedtime. They usually came on in mid-fall at the beginning of November. They were something to look forward to in a time when The Internet and streaming movies online weren't even a glint in The Matrix’s eye.

This is what Stranger Things really reminded me of the most while watching it. It felt like a Sunday Night Stephen King TV event from the 90s, but without commercials, a lot more episodes, and a whole lot more character development. Stephen King’s love for endless flashbacks that delve further into past events of the story and characters is on full display in Stranger Things (Spielberg and Lucas never really have flashbacks), as is his signature tropes and cliches of shithead bullies and unrequited crushes.

But the biggest tribute to Mr. King is the character of Jonathan Byers. He is the ultimate sensitive loner right out of a Stephen King story. He’s shy, smart, creative, kind, and (of course) has a huge crush on the cute girl who (of course) is in love with a total asshole. How does he cope? He’s got amazing taste in music, a set of headphones, and a camera with real film that he takes real photographs with which he develops in a real darkroom (remember those?)

He’s the kind of character a lot of us relate to who hid out in the library instead of going to P.E., read books about ghosts, Mothman, and UFOs instead of partying all night or going on dates, drew pictures of forests and aliens in our notebook, listened to Joy Division and The Smiths when the rest of the world was listening to something horrible.

I connected with Jonathan Byers the most out of all the characters on the show. He even knows about The Smiths in 1983, a full year before their debut album came out in 1984 which would've been impossible, especially for a kid living in Whereverville, Indiana in the early 80s. Jonathan’s also a great older brother and surrogate dad, teaching Will about “the good music.” The flashbacks with Jonathan and Will are touching. I kept imagining Jonathan discovering Kraftwerk, Suicide, Throbbing Gristle, and Cabaret Voltaire at some point a year or so later and sharing his weird discoveries with Will who still might be hung up on The Clash and The Ramones.

Having our favorite character into New Wave is a heartwarming move on the part of The Duffer Brothers. Just about everyone born between the late 60s and 1980 who was into UFOs, horror movies, and Stephen King most likely became a New Wave kid in some form or other. Spielberg’s films are strangely devoid of anything New Wave or punk. The closest thing to a New Wave music moment in any of his films is The Jim Carroll Band’s “People Who Died” being heard in the background as the kids are waiting for the bus in E.T., and a mention at the end of Poltergeist by the mom that the white streak of fear in her hair “looks kinda punk?” (her oldest daughter rolls her eyes.)

The teenage characters are more interesting in Stranger Things than the younger kids. They feel more complicated and mixed up than the twelve year olds who, though refreshingly angst-free with their BMX bikes and flashlights, seem understandably idealized in order to move the action along in a conventional genre sort of way, albeit a fairly satisfying way.

The teenagers soon become wrapped up in the action in a crucial way as the show rolls along too. The kids, the teens, and the grownups all come together in a not altogether expected way as the show reaches its climax that I can’t say I’ve seen before in Spielberg or King. There’s always a kids versus the clueless adults ethos in both Spielberg and King. Not in Stranger Things. The grownups are good guys too… well, some of them.

The show deviates from Stephen King by not being nearly as depraved or violent as his classic books. The bullies don’t get horribly killed and mutilated like in Carrie or IT, there’s no evil, bigoted evangelical christians, and there’s no dead children... not really because Will is rescued at the end. The bullies get what they deserve, but they’re not wiped off the face of the Earth in blood and fire (one pees his pants, the other gets his arm broken later on; both incidents a result of Eleven’s scanner powers, both moments acts of self defense.)

So, Stranger Things is a lot sweeter than the nightmares of Pet Sematery or The Shining. The families become stronger at the end, not torn completely apart, and the underlying anger of Stephen King toward protestant Middle America isn't anywhere in sight in Stranger Things.

Stephen King's IT (1990)

Stranger Things does adhere to the cliches and conventions of Stephen King in one very disappointing way, however. The ending’s a letdown. The creature isn't nearly as scary when we see it full-on (it looks like the final stage of Brundlefly combined with the plant from Little Shop of Horrors), and the battle between it and the kids isn't nearly as exciting or suspenseful as the events leading up to the climax. After seven plus hours of build up, it’s pretty disappointing that the creature is subdued with a slingshot, just like the monster at the end of Stephen King’s IT. Like virtually every Stephen King book and film adaptation, the buildup in Stranger Things is a lot more engaging than the final battle. The evil creature dies too easily, too quickly.

All this is forgivable since there are a few unexpected surprises that save the series from total disappointment. Remember Steve that asshole boyfriend with the Johnny Marr pompadour (before Marr turned it into a Brian Jones bowl cut)? After getting the shit whomped out of him by Jonathan a few episodes prior, Steve the jerk sees the error of ways and apologizes, sincerely. He joins Jonathan and Nancy on the quest to kill the monster, and all three of them become a team just like the twelve year olds with Eleven the scanner.

Then, a few months later in an epilogue after the harrowing adventure, Nancy is still with Steve. How can this be??? We’ve been betrayed! Just like real life! Yet Jonathan and Nancy’s bond is stronger and beyond anything unrequited, becoming brother/sisterly rather than romantic. She gives him a new camera for Christmas (Steve busted up his old one upon learning that Jonathan was being creepy and stalkery with it.) This is a lot different from what we’d expected from the shallow preppy dramas of John Hughes. Steve the jerk isn't James Spader after all. He turns out to be human in the end with a big heart. Maybe Jonathan and Steve will form a band. Maybe next season.

Silver Bullet (1986)

Chapter Four: Whereverville, USA

Stranger Things takes place in Indiana, but was filmed in Georgia. A lot of Close Encounters of the Third Kind takes place in Indiana, but was also filmed Georgia. E.T. was filmed in The San Fernando Valley. Poltergeist was filmed in Simi Valley just a bike’s flight over the hill from where E.T. was filmed. Most of Stephen King’s books take place in Maine, but all of the De Laurentiis Stephen King film adaptations from Firestarter to Cat’s Eye, Silver Bullet (Daniel Attias, one of Spielberg’s assistant directors on E.T., directed Silver Bullet), and Maximum Overdrive were filmed in Wilmington, North Carolina.

All these places, though actual places in the world, were created by their filmmakers to represent a specific fictionalized realm, a cinematic setting of middle class white America: the suburbs. Suburban America took off after World War II virtually simultaneously with the viral spread of television and fast food. The Post-War middle class of the Baby Boomer generation, because they had stable jobs, a car (or two), a house, a yard, and a general sense of economic security, had more free time on their hands than any previous generation in America.

They had fixed work schedules.They had weekends. They had vacations. They had holidays. They had barbecues. They had a TV and sometimes they went to the movies. They traveled the world through the pages National Geographic. They lounged in long ago, far, far away lands via the faux exotic records of Martin Denny and kooky Polynesian themed cocktails. They explored the past and went into outer space and humankind’s future thanks to Walt Disney, all without leaving the comfort of their living rooms or backyards. Maybe they even went on a real trip once a year to a national park that they saw on TV or in National Geographic.

In all this fantasy, all this leisure amidst the blandness of Suburbia and the corporately manufactured standards of this new lifestyle, childhood and adolescence became idealized, romanticized, and sentimentalized in ways that had never before been seen in history because in Suburbia, kids and teens were now a whole new demographic to sell things to. In America, childhood and adolescence are concepts dreamed up by a marketing firm.

Supercomputer (1981)

And yet, despite all this prosperity, all this high standard of living, a longing still lingered within Post-War Suburbia; a creeping skepticism that there had to be more out there, better art, real places, real people, maybe even haunted houses down the street, maybe even aliens in the woods.

This longing for new fantasies with roots in the day to day realness of life and its clash with the banal prosperity of Suburbia is where people like Stephen King and Steven Spielberg and their fictional worlds were born. Both artists are the same age, from the same Post-War generation, and though both came from different regions of America, both come from the same zeitgeist. The suburbs of the 1950s and 60s may have represented American prosperity and our superiority over those dirty commies, but they were also the pits! The houses all looked the same, every mom had the same hair and wanted to be Betty Crocker, and dad worked too hard and drank too much. The suburbs revealed a boxy, packaged idea of prosperity, often with onerous realities not far beneath the surface.

Meanwhile, kids like Stephen King, Spielberg, and George Lucas were dying of boredom, looking out the window into the clouds during math class, dreaming of getting out, making movies with their dad’s Super 8 on the weekends, writing ghost stories to freak out their friends, and building their own haunted houses in the backyard. Without the sterility of Post-War Suburbia and all its dullness, we might not have Carrie or Salem’s Lot or Star Wars or E.T. since the creators of those things developed a need for them out of sheer, stifling boredom.

King’s tales are a rebuke and condemnation of Suburbia full of bullies, sadists, gore, and pure evil. Spielberg’s early films aren’t so much a celebration of the suburbs as they are a perfect setting (E.T. probably wouldn't have worked as well in downtown LA.) Because of their banality, the suburbs are a blank slate for something magical to unfold which leads to humor, mild irony, suspense, and wonder. And George Lucas’s stories are a flight from Suburbia entirely, though it’s not hard to see that Lucas’s world of alien planets isn’t all that different from something very suburban. Going to another planet is like going to the park down the street or over to another neighborhood across town.

So what does Stranger Things tell us about today’s Whereverville, USA? The big thing is that it tells us the suburbs don’t really exist anymore in the way Spielberg used them as a sandbox to inject his own adventures and fantasies. There are still suburbs today to be sure, but not like Spielberg’s, not like the 80s. The Spielberg suburbs are now a total fantasy, which is why Stranger Things takes place in 1983 Suburbia, not 2016 Suburbia.

Though Stranger Things is a love letter to The Duffers’ favorite movies, it could not have been made in the 80s. It may wink towards the past, but it is undeniably of the now despite it beating its chest that it takes place in 1983. 1983 in Duffer World looks different somehow than Spielberg's suburbs, more real in its brown frumpiness (which they nailed), but somehow very "now" a lot like how the 50s Marty travels back to in Back to the Future looked weirdly more "80s" than the actual 80s.

Who Killed Harlowe Thrombey? (1981)

Strangely enough, I kept trying to imagine the show taking place now instead of back then, and it just didn’t seem to work the same. Is the sense of neighborhood camaraderie that’s at the heart of Stranger Things the perfect fantasy for Millennials and Post-Millennials fed up with the exhausting demands of social media and all its unfettered, constant narcissism just like the pages of National Geographic and the fake frontier Americana of Walt Disney’s Davy Crockett were an escape from the mundanity of the suburban staleness of the 50s? I think so. If our Instagram accounts are to be trusted, Stranger Things has struck a real emotional nerve in people… if only for a few weeks.

The lasting impression of the show will be interesting to track. In this era of binge watching and Snapchat, the idea of anything hanging around for years and years to be analyzed and consumed then reborn in some other form down the line through inspiration and influence seems passé in this swipe and scroll, click and like society. The idea of criticism and analysis seems passé too. Longwinded essays like the one you’re reading at this very moment seem passé. Everything is available now, on the spot, instantly, anywhere, at any time. There’s no absorption, no cultivation in the vain manner Gen Xers liked to martyr themselves over in their day.

The stereotype of the cranky, romantic New Waver, the idea of the ranty, unquiet, elitist Generation Xer who earned their right to love Devo and Star Trek, Skinny Puppy and Fangoria after getting repeatedly picked on during lunchtime for their less than popular tastes throughout high school seems more and more quaint and dated now since everything is so accessible today. All is permitted. What you don’t like, ignore. What you do like, click a heart on your phone’s screen, and keep scrolling. There’s no time to be precious about anything and grouchy about it. That stuff’s for Generation X, right? There’s Pokemon to be caught and selfies to be drawn on. "I am Millennial, hear me scroll!"

I wonder what the future holds. Where is this gluttony of self-reflexive media headed? Maybe the idea of “the future” is passé too. Maybe social media is the new suburbs: mundane, endless, boring, yet, unlike Baby Boomer Suburbia, no escape in sight. Stranger Things and its pre-internet setting might be the perfect escape Millennials crave that’s filled with the sort of meaning Gen X found in stuff like Close Encounters and Raiders of the Lost Ark. For Millennials and Post-Millennials, there’s probably nothing nostalgic about Stranger Things at all, just as Indiana Jones wasn’t Nostalgia for people who hadn't grown up with Saturday afternoon serials (Saturday afternoon serials were a little before Spielberg and Lucas’s time too, by the way.) Stranger Things to them is the real thing, its faux Struzan cover art glittering jewel-like like a chandelier in The Temple of Doom.

Besides, who wouldn’t want to escape this world full of police brutality, economic disparity, the collapse of education and intellectualism, and the most muddled, confusing, and depressing political climate the modern world has ever seen and instead go into a world of telekinetic children, monsters, environmentally irresponsible hair products, rad music, dinner at the table every night, and no social media to speak off? Yeah, sometimes I really miss my old bike and D&D friends with all my heart. Don’t you?

E.T. the Extra Terrestrial (1982)

Chapter Five: A Demogorgon Called Nostalgia

Just what is Nostalgia? People use that word a lot, and everyone seems to have a strong feeling of what that word means, yet no one ever really talks about what the term really means and how it affects a person’s tastes. It’s a difficult topic to discuss because it goes to the very heart of people's deep rooted emotional attachments to things and events. It has to do with feelings more than the intellect.

When I talk about Nostalgia and my skepticism of it as a creative mode for a story, film, or other work of art, I’m not talking about all those wonderful people I follow on Instagram who enthusiastically collect old VHS tapes, who love films and books from a past era, old toys and action figures, comics, or fantastical kitsch. I consider these people historians, archeologists of the past who may not have been alive when those things were even made, yet their voracious collecting and curating informs their present lives in a real, meaningful way. That’s not exactly what I mean by Nostalgia in the context of this article. Nostalgia is a strange phenomenon having to do with Post-War Americana, materialism, and consumerism and how it complicates, beguiles, and confuses actual history: The Internet making it even more complicated and difficult to pin down.

An important aspect of Nostalgia is that, like Freud’s concept of The Uncanny, it produces a reflexive, spontaneous, convulsive response in a person. You just can’t help it. Like the other day I was in Home Depot and one of Huey Lewis and the News’s goofy songs came on. I know Huey Lewis's music sucks, but for some reason I sorta like it. I never actively listen to him, and my good taste tells me to despise the yuppie Patrick Bateman type people who ate up that kind of music in the 80s. Yet there I was, delighted and revolted in the same instant: true abjection. I was instantly transported back to the fourth grade. It was a Friday after school. My mom was making me a frozen pizza. She rented A Nightmare on Elm Street for me. That’s Nostalgia. I was powerless. I didn't seek out that experience, it just “happened,” and I was helpless, caught in the throes of a horrible song and a beautiful memory, my arrogance and good taste thwarted in the same instant.

This is one of the multiple heads of the Demogorgon named Nostalgia. It’s a wholly different, though connected, creature from history and even memory because Nostalgia, unlike real history and actual memories, can be reproduced over and over again: the copy of something perhaps once rooted in a real thing, in real history, that the person experiencing it might not have even experienced first hand when the real thing actually happened.

But unlike The Uncanny, Nostalgia isn't vague or mysterious: it’s specific. It's canny, NOT uncanny. Nostalgia is theoretically a dangerous thing for the progressively minded since it coaxes you to go back rather than forward. Nostalgia is sometimes inevitable since something always inspires something else. Nothing happens from nothing.

The question, then, is how far is a work of art using those past elements to do something different within an art form without making an uncanny corpse-like copy? It’s a tough question these days for artists. Stranger Things walks a very narrow line. As I’ve said earlier, Stranger Things is contemporary in many key ways despite its 1983 setting. But it still, paradoxically, is completely, symbiotically, even parasitical dependent upon the past. Is it Nostalgia, or is it a clever bighearted pastiche? Is it live, or is it Memorex? It’s both, some episodes intertwining this disparity better and more cleverly than other episodes.

Poltergeist (1982)

Furthermore, Nostalgia is truly insidious and differentiates itself from history and memory in this fundamental way: it makes you want to go back to something that you can never go back to, or worse, it can make you want to go back to something that never existed to begin with, like one of those awful Thomas Kinkade paintings that look like they belong in the office of some Nazi dentist instead of Grandma’s house. Nostalgia is like the upside down moldy shadow realm where the Demogorgon lives in Stranger Things. It mirrors your reality, your past, but in an altered way that doesn't quite line up with actual reality.

But having a genuine love and interest in the past or a past aesthetic or ethos is not really Nostalgia in this sense because being interested in something and learning about its history doesn’t mean you want to go back to the time it came from. The past can inspire you in the present, motivating you on some fundamental psychological, spiritual level that isn't "nostalgic." That's reality, not a daydream.

None of us are immune to the siren song of Nostalgia, and many of us actively avoid it, though sometimes in vain, preferring to acknowledge something from the past in and of itself rather than as some vessel to transport us back to another age when times were sweeter or better. The reality is, no time was better or sweeter. Human history is stained with blood, cruelty, superstition, paranoia, and tragedy. Contemporary times are no different. We just have a way to Instagram about it and yack on Reddit in a way past cultures didn’t. I love a lot of the music and movies from The 80s, but let’s not forget there was a lot more crappy movies and even crappier bands back then than there were great ones.

Isn’t it funny how we only remember the good aspects of culture from a past decade forgetting that back then things which were really great were as rare as they are now? It’s funny that Happy Days (what a simple, ingenious, and unintentionally ironic title for a show about Nostalgia for Nostalgia’s sake) never had a single episode about the racial inequality of The 50s or the witch hunts of Joseph McCarthy. The Demogorgon called Nostalgia has such a cruel sense of humor.

Twin Peaks (1990)

In Post-War suburbia, Nostalgia became a big thing along with the TVs, the well watered lawns, the cars in every driveway, and all the immaculate track homes, which is funny because prior to World War II there were so many tragic hardships that it’s hard to imagine why anyone would think something like The Great Depression was “better times.” In this environment of such material consumption, manufactured Nostalgia was the perfect drug since Nostalgia is a missing sort of feeling produced by an artifact of entertainment, usually kitsch in nature, rather than merely a fond memory of a past event or even a fondness for the past. A feeling of yearning and “I want go back, but I can’t and that sucks” has to be present to be true Nostalgia in this context.

There’s a resentful quality to Nostalgia. As Milan Kundera said in his novel Ignorance, “The Greek word for ‘return’ is nostos. Algos means ‘suffering.' So Nostalgia is the suffering caused by an unappeased yearning to return.” And because Nostalgia can be produced in a factory and sold over and over again, the American middle class has a complicated relationship with it more than I suspect other cultures do, the true meaning of the term Nostalgia itself getting muddied, confused, and overused along the way, The Internet further complicating the difference between the pain of wanting to go back and just liking something that happens to be old.

Plus, there are many, many cases in my life where I thought something was kind of sucky, then years after the fact realizing how great that something really is. Like the movie Krull. When I was seven years old, I thought it was the dumbest movie ever. I didn't get it. But when I saw it as a grownup, I loved it. Krull’s better NOW to me than it was back then. Time’s funny because it can sometimes make certain things better, even the past. Is that an aspect of Nostalgia too? Another form of the Demogorgon? Nostalgia in reverse?

Here’s the good news. We don't have to go back. We don’t have to be taunted and teased by the Demogorgon. We can resist it. We can go forward. We can revisit the past anytime we want to with our thrift store bought VHSs, our vintage movie posters, our synth pop and post-punk records NOW without ever feeling the pain of wanting to go back. That’s the beauty of great art. It was made THEN, but it lives NOW, and it will live long after we’re no longer here to post about it on social media. Who wants to go back to their high school years anyway? High school was horrible.

From left: Dreamcatcher (2003); Strange Invaders (1983)

Chapter Six: Stranger Things

I’ve said earlier Stranger Things could not exist as a show made in The 80s. The reason for that is because of the advent the binge series where the entire season of a TV show unfolds over eight to a dozen or so episodes landing all of a sudden like the troops at Omaha Beach. It’s been said before, but the invention of the binge series has made going to the movies a real drag. I love going to the movies, but it’s really tough for me to remember anything in the last five years that made me cry the way the Hold The Door episode on Game of Thrones did, or made me say out loud “AMEN!” to something Elliot says on Mr. Robot during a movie at the theater.

Movies today are still great, but there’s an in-depth narrative commitment and emotional involvement that today's binge series have that few mainstream movies can match since most movies are only two hours long... then they’re over forever (unless they're, God forbid, rebooted, or given an unnecessary sequel decades after the fact.)

Watching a serialized show these days is different. They’re like reading a novel or an entire series of novels: a potent, sometimes operatic hybrid of cinema and literature that has never been seen on this Earth before, not even by the BBC in the 70s. American TV series like Dynasty or Dallas back in The 80s may’ve been serialized, but there was a hokey soap opera-ness about them that made them campy and repetitive at a certain point. Game of Thrones might also be a soap opera, but it’s a soap opera that only Kurosawa or David Lean could’ve conceived. Stranger Things is no different. It’s great that it unfolds over eight hours even if the outcome is a little anticlimactic. It’s somehow better being stretched out over eight one hour episodes (I thought it got better actually as the episodes rolled on.)

Binge series beg you to get involved even when you’re reluctant. "Maybe the next episode will be better," we ask ourselves. If Stranger Things had been thrown together into a two hour theatrical movie, or even a three hour, two night miniseries with commercials, the response to Stranger Things would not be as overwhelming as it is. People today want sagas, uninterrupted, without commercials, with a diverse ensemble of characters, and they want to watch it at home, on their own time. The days of Aaron Spelling and waiting a whole week for the next installment are dead. Movie theaters are dying too. The content of television today is astounding. I wonder if the bubble will ever burst. When will all this great TV stop? Hopefully never. But if it does, I’m just going to binge watch it all over again.

So the key thing, really, of why people are loving Stranger Things so much is because there is nothing at all ironic or smirky about it. It’s not a De Palma or Nicholas Winding Refn movie. It’s not Tarantino. It's not smartassy. It wears its influence on its sleeve, and the lack of nudging irony, this earnestness about it all, is what people are responding to so wholeheartedly even when some of the show’s influences are being waved in our faces like E.T. throwing gang signs. Yes there’s a scene where the science teacher is watching a scratchy video tape of John Carpenter’s The Thing, and there’s a part where Eleven levitates a toy Millennium Falcon with powers not at all unlike E.T. levitating the Play-Doh. Yet, these sort of things are innocent, not vulgar or ironic. After all, the kids in Poltergeist had a Star Wars and an Alien poster on their bedroom wall, and Elliot in E.T. had a menagerie Star Wars stuff too, just like the kids in Stranger Things, just like any kid in the early 80s.

But the show’s strength, like Yoda tells us, is also its weakness. Some of us so steeped in the lore and aesthetics of that era which Stranger Things is so obviously paying tribute to will be annoyed in the same blink as we are amused by it. I guess it’s our loss for shrugging and rolling our eyes at something that only wants us to like it and be entertained.

Charlie Heaton as Jonathon Byers in Stranger Things (2016)

Stranger Things is this generation’s American Graffiti, George Lucas's 1973 complete 180 from his previous flop (and best film) THX 1138: hip retro-ness filtered through contemporary values and styles of that time's era that's simultaneously a loving rememberance of a past time. Instead of the milkshakes, hotrods, jukeboxes, doo-wop, teenagers trying to con the guy at the market to give them liquor, and Ron Howard, Stranger Things has BMX bikes, Dungeons & Dragons, government agents, a clandestine conspiracy of some sort, paranormal powers, a monster on the loose that can move through walls, Winona Ryder, and a hip older brother that’s into The Clash, Television, and Joy Division.

For all of American Grafitti’s seeming retro-ness, however, it too (like Stranger Things) is a product of its time wearing on its sleeve the influence of Jean-Luc Godard more than the influence of any cornball teen movie from the actual 50s. Both things are sophisticated escapism made by hyper-aware, over-educated pop culture film nerds; smart escapism transporting us from the troubled, complicated present without completely forgetting about the present.

So, maybe we need Stranger Things the way people needed The Beatles after the JFK assassination, the way people needed Star Wars after Vietnam and the Nixon debacle, or the Harry Potter movies after 9/11. Perhaps Stranger Things is more like Donnie Darko which galvanized and polarized a generation in a culty sort of way in the final days of the video store era than anything Amblin produced in the 80s (Donnie Darko is itself a pastiche of sorts of Stephen King and Spielberg set in the 80s with New Wave soundtrack awesomeness in practically every scene.)

The strangest thing about Stranger Things is that any sort of critical backlash seems to be fairly quiet. In perfect Millennial fashion, people are either loving it (or just saying they love it in order to have something to post about on social media), or just ignoring it altogether since involved opinions and deep analysis aren’t all that PC these days. The most interesting thing is that the most fervent of the show’s fans seem to be people who weren't even alive to experience the real thing first hand, let alone born yet to experience the zeitgeist which birthed these American middle class fantasies, fantasies which, like Poltergeist and Gremlins, were profound metaphors of American Suburbia and just how dark and hypocritical it can be. There isn’t a single bit of satire or irony in Stranger Things. That’s a strange thing indeed for anything these days.

I wonder, would a fortysomething Jonathon Byers be rolling his eyes while watching Strangers Things in 2016 and scoff at the show’s “inspirations” just like the hardened Gen Xer he’s shown to be becoming in Season One?

Poltergeist (1982)

Chapter Seven: Other Things

If Stranger Things makes me long for anything, it’s not for a time where things were necessarily simpler. The 80s, lest we forget, were a terrible decade filled with illegal wars, rampant drug addiction, economic inequality, the threat of nuclear devastation looming everyday, new diseases threatening entire subcultures, celebrities famous for absolutely nothing at all, the worst politicians that have ever slithered upon the Earth, and stifling, unapologetic, shameless, soulless materialism. Doesn’t sound that different than today, does it? Nor does the show make me long for a time where movies and TV were “better,” because I don't think films and TV (especially TV) were in fact better back then. There’s plenty of great movies out there today like Ex Machina, Beasts of No Nation (also on Netflix), and The Revenant that don’t allude to other aesthetics of past cinema eras (even Ant-Man’s pretty neat in that regard.)

Not to mention, there’s more excellent contemporary TV out there than any adult human with any semblance of a life could ever possibly have the time to watch in its entirety. There’s more Wire, Bauhaus, Coil, and Throbbing Gristle fans today than there probably ever were Huey Lewis and the News fans back in the day (ugh… that dreaded expression, “back in the day.”) So today's art and entertainment isn't really so awful that we must yearn for another time’s creations, especially when all those films and TV programs are readily available on every streaming service, legal or otherwise, at the click of a button or a drag of the finger, and all those bands which were impossible to find are all right there floating in The Matrix somewhere.

What Stranger Things makes me miss isn’t the films, TV shows, and books from a time already passed. What it makes me miss is a time that wasn’t so preempted, negated, and dependent upon The Internet, a time where things could be absorbed and cultivated, where tastes could be refined and explored without The Internet cancelling out or meeting us halfway (or even all the way) with its aggregated judgement of an artwork or piece of entertainment that it deems worthy or unworthy of more than a day’s attention before anyone has had a chance to experience it for themselves and make their own mind up about it.

Even as you read this, I’m fairly certain this article about a show that exploded across social media a few weeks ago isn’t even relevant, the enthusiastic Instagram posts accompanied with pictures of that undeniable glowing red logo getting less and less frequent in my feed, the initial ecstasy of a show everyone was so giddy about a few weeks ago fading away like a distant UFO into a boiling cloud bank forming in time-lapsed blue screen glory.

My So-Called Life (1994)

The Internet is the big cultural Death Star of our times, the thing that seems to promote fevered fandom for things not experienced the first time around, but which actually destroys them in an endless barrage of blogs, YouTube posts, Reddit threads, and half-hearted listicles before anyone can really judge the things for themselves and really dive into them on their own terms. Yeah, there’s something for everyone these days, but nothing new.

On the other hand, maybe The Internet isn’t The Death Star at all, but a great sentient ocean like Solaris, a planet-sized alien sea of immeasurable intelligence and mystery, a being which tries to communicate with us by generating ghosts from our unreconciled pasts which, the phantoms being too real, the memories too painful, drive us mad instead of giving us meaning as little E.T. or even The Monolith in its super goth, aloof, abstract way gives us meaning.

The haunting entity of Solaris and the deadly power of The Death Star are like The Internet in that they are both anticlimactic destroyers of expectation. Solaris doesn't give us the sort of catharsis we crave and receive from Close Encounters or E.T., just more mystery, heartbreak, and longing. And The Death Star which menaced the galaxy throughout the entire film of Star Wars is blown up far too easily at the end than it probably should've been. Stranger Things might be the perfect product for this Internet world, a show which teases and gives us what we want, what we always wanted, just like the original sources it so zealously and heinously is inspired by.

The tough question then for anyone watching the show with the inborn incredulity of any dutiful Gen Xer is this: is that so bad? Is it really so awful to have a thing that relishes in a past style and does it with such obvious love and positivity for the things it’s in love with, and then does it in an entertaining way? It’s up to the individual. The human race isn’t totally a hive mind quite yet. Some days we want pizza, other days we want filet mignon, some days maybe a salad, some days maybe we’re not even hungry. That’s life in this Mad Max wasteland of limitless choices and easily fulfilled desires.

Gen Xers are a snobby generation. They're opinionated, skeptical, and just can’t shut up about it. Millennials aren’t. They just go with it. They’re free from a lot of the things Generation X were oppressed by, but nagged by things that don't occur to Gen Xers.

I wonder, what will they remember fondly once their time has passed, when the generation just behind them is in charge? And what will Post-Millennials do? Will they flock around a shiny black rectangular obelisk like protohumans in the desert, awaiting a great convergence with The Overmind? And what of the generation after? Will they flock around a shiny rectangle they can hold in their hand, an artifact from a past era which they'll horde the way some people today horde old video tapes, sentimental for a past time when times were simpler, when The Internet still existed in a more primitive state?

Chapter Eight: The Frozen Future

And finally, one day all this will be passé too: smartphones, Snapchat, wearing Slayer shirts because you like the design even though you’ve never heard the band, binge series, online streaming, Reddit, all of it. Millennials will be old too some day, their culture of gleeful, eclectic consumption, their selfies, their Pokemon GO triumphs and heartbreaks, their emojis and txt abbrvs all buried under the same ice that will bury everything else of humanity.

And when aliens which will be evolved versions of the robots we invented to explore outer space return to their home planet of Earth thousands of years from now and excavate our civilization from under the miles and tons of ice, perhaps they’ll find a child’s skeleton clutching a smartphone. And from the data contained within that strange little rectangle, they’ll build their own mythological pastiche of our faded world to tell their cybernetic children about a world that loved to build things and worshipped the past just as The Duffer Brothers have built their own saga about a past world they love so much.

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)

Lawrence Pearce is a writer, musician and artist living in Los Angeles. (@novemura)