By Lawrence Pearce

The Terminator, 1984. Directed by James Cameron

Part One: The Day After

It was November 20, 1983: the Sunday night before Thanksgiving. A TV movie unlike any other aired. Part warning, part anti-nuclear political statement, part cornball melodrama, but entirely devastating and traumatic, especially if you were in the beginning years of elementary school when you saw it, Nicholas Meyer’s The Day After changed many people’s lives forever, and even changed the nuclear policies of two superpowers.

Filmed in the beige blandness that characterized Middle America of the early 80s, and featuring no real “stars,” The Day After felt real in a way no other atomic holocaust movie ever had before. The people in it felt like people second grade me knew in real life, as did their weird perms, tight high-water jeans, dolphin shorts, knee-high socks, and tucked in IZOD shirts. It didn’t feel “like a movie” to my 7 year old mind at the time. I knew it was fictionalized, but this perceived realness, however naive, freaked me out like no horror movie or Stephen King book ever had, or ever will, before or since. Poltergeists, teenagers possessed by demons, vampires… All that stuff was fantasy. Even I knew that as a kid. But nuclear war? That was real. Still is!

Then, a little over halfway through the film, it happens…

Something goes wrong. An irreversible military offense happens in Europe to NATO forces in Europe or some such (we never really know definitively how the war starts in film, only that something starts it off and there’s no turning back), and both sides launch their nukes. Citizens of the small town in Kansas where the story takes place look up in horror and strange awe as the missiles launch into the blue sky towards their overseas targets.

The Day After, 1983. Directed by Nicholas Meyer

Then everyone braces for the inevitable. The Soviet Union has certainly launched their nukes too. Everyone seeks shelter, vainly. There’s a flash (one of many going off simultaneously throughout the country), a rumble, the fear of God setting in. The EMP from the initial air burst makes everyone’s electricity go out. No one can drive away because it kills the cars’ systems too, then… BOOM!!! Some directly in the blast wave fry completely, their skeletons visible for a split second in the glowing red air before scorching to nothingness. Buildings shatter. Forests turn to dust instantly. All of civilization and human history swept away forever in the instant it takes to snap two fingers together. Those who survive have a dead world to wander aimlessly — stunned, grief stricken, burned, sick, driven mad, blind, scarred, the soil and water poisoned for generations, nuclear fallout flutters to Earth like snow, filling the air like moths, collecting everywhere, giving those lucky few who survived the blast radiation sickness they will never recover from.

THE END.

Part Two: Survival

Hardware, 1990. Directed by Richard Stanley.

Did the kids in Stranger Things watch The Day After??? I know I did! I saw it with my parents, and it shook me and many people who saw it that Sunday in the fall of 1983 to our very core. My dad scoffed at it. My mom chuckled and thought it was stupid. “It would be way worse if it really happened,” she said (thanks Mom.) I was never the same again, and though it’s dated today and inferior to its much better atomic drama counterparts of the same era, the theatrically released Testament and the BBC’s more horrific Threads, The Day After was the one whose shadows got burned into my brain first. And while the threat of nuclear war seemed inevitable to us kids from that time, our mind sought out alternatives; collective fantasies to escape into that made the inevitable bearable. Imaginary places where the post-nuclear hell of disease, starvation, poisoned crops, spontaneous cancer, ruined buildings, gangs of marauders, and wasted civilization became a fantasy world filled with violence and horror to be sure, but also high adventure. Maybe the end of the world could be exciting and mythological, not depressing and miserable. Maybe humans would have a chance.

The Day After, 1983

There’s an entire subgenre of action films that are a product of this global nuclear fear. The second and third Mad Max movies turn the post-atomic apocalypse into a futuristic Spaghetti Western filled with poetic but grim Kurosawa nobility and pathos, rad vehicles, and old fashioned medieval chivalry and self-sacrifice.

Red Dawn is a right wing fantasy action film where communist forces detonate only a few strategic nukes, but decide to invade the continental US with troops, tanks, and helicopters instead of burning everything thing to the ground with nuclear missiles leaving the occupied citizens to get herded into POW camps or fight as resistance fighters in an endless series of exciting cowboy and indian-like chases and battles. Sounds so much more fun than bleeding from your gums and anus while spending your final few days blind from the nuclear blast, huh?

Red Dawn, 1984. Directed by John Milius

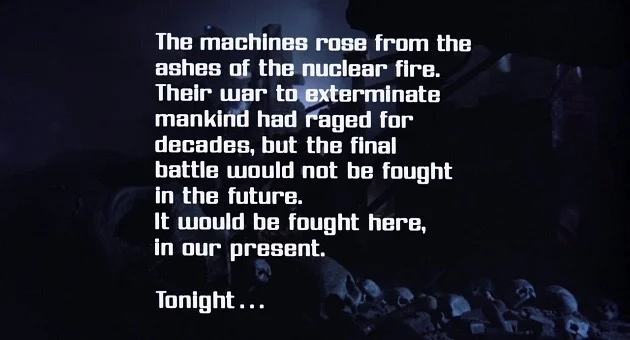

But the ultimate alternative nuclear fantasy is James Cameron’s The Terminator where time travel is used to avert (hopefully) a nuclear judgement day altogether. We see brilliant little glimpses, flashbacks, suggestions of the post-apocalyptic world where the remnants of humanity battles the robots that destroyed the world, a place where children huddle around a fire in a broken TV set to keep warm (such a beautiful visual metaphor), but it’s mostly a tight genre action movie that takes place in the then modern day of 1984 ripped from the same cloth as John Carpenter’s Escape From New York, itself a dystopian western with implications that the police state at the center of the story is a result of some futuristic world war.

Part Three: The Sound

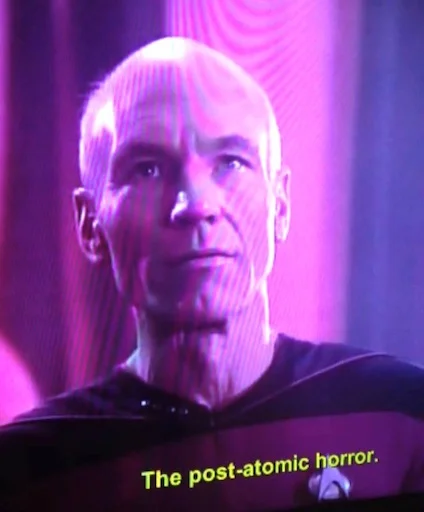

Encounter at Farpoint, 1987. Star Trek: The Next Generation

And yet, all these fantastic apocalypses, these adventures, needed a soundtrack; musical accompaniment to express the feelings the characters couldn’t say, and which the visuals didn’t show. Not just for the movies themselves, but for the entire culture as a whole that spawned these fantasies of the post-apocalypse. Red Dawn and the Mad Max films have great music scores, but they follow typical action-adventure motifs with lush orchestral arrangements. There needed to be something else, another medium, which was also a fantasized, however horrific, paradigm about the world after it ended in nuclear holocaust. There needed to be a music genre, bands, that expressed these collective post-atomic fantasies just as cinema had done with Mad Max. What would it sound like, exactly? Punk? Metal? All great candidates, but there had to be something else that fit the blasted wasteland in our heads that was populated with cyborg skeletons with glowing red eyes and samurais riding on pterodactyls wearing armor made out garbage.

Moebius's Arzach, 1977

Generally speaking, classic punk rock — though no doubt dystopian, harsh, bleak, and fittingly apocalyptic in many ways — somehow never seemed darkly futuristic enough to be this particular sound because, in the best sense, it’s essentially still rock and roll working class music violently screaming its destain for bourgeois mediocrity, always more “right now” than “30 years since the end of World War III.” And the operatic onslaught of heavy metal was definitely suitably apocalyptic sounding, though its Tolkienian bombast always felt more like The Middle Ages than The Nuclear Ages. There had to be a clanking, synthesized, cold but not unfeeling, throbbing sound out there somewhere. Something like The Terminator soundtrack, but not exactly cinematic and not wholly theatrical in the way heavy metal tends to be. Something electronic. Something harsh, but atmospheric. Something that sounded like the sort of thing you’d hear while warming yourself in the fire of the hollowed out TV set in some resistant fighters camp as the genocidal robots marched in.

Then, we found it.

Bands like Front 242 and Skinny Puppy had this perfect sound: Front 242 with their paramilitary theatrics, stormtroopers and commandos patrolling the dystopian metropolis rebuilt from the nuclear ashes of World War III in their SWAT gear, armored vehicles, and elaborate head displays… and Skinny Puppy, the mutant horde camped out around this metropolis, a neo-tribal nightbreed of deformed humanoids, their encampments and villages made out of skeletons, burnt wires, car parts, and bloody parachutes, a tiny fire in every dead TV set, their clothes fashioned out of tires and old luggage. This was the sound we craved.

Akira, 1988. Directed by Katsuhiro Otomo

So in this day and age when one single unifying fear of global devastation doesn't affect an entire culture in the way the threat of nuclear war disturbed previous generations, is there still a desire for post-apocalyptic fantasies if no one is really afraid of the world exploding all at once? We don’t have just one enemy today, but several. There isn’t just one disease to wipe us all out, but many. Do people still fear a global catastrophe in the way people did the 80s? And if so, do people still want to escape from this possible reality by inventing mythologies that imagine a livable but still brutal post-global holocaust world — a world, however fantastic, that’s still rooted in real fears of impending doom without seeming quaint and nostalgic.

Part Four: Pure Ground

A Boy and His Dog, 1975. Directed by LQ Jones

A band like Los Angeles’s Pure Ground says “YES.” Their sound is a grinding, mechanical sort of humming, like the terminator warming up. It’s agitated like the radioactive dust rattling off of the metal shell of an assault vehicle as the engine roars alive to explore the nuclear desert. It’s cold like the poisonous snow that’s fallen on a field of charred skeletons — soldiers who died bravely in the robot apocalypse.

Yet, there’s a heroic romanticism to Pure Ground (a name that evokes soil that hasn't been polluted with fallout) amid all this grayness and decay. A track like “By The Grace of God” on their new album Giftgarten sounds as much like the hymn of a pilgrim venturing out of the bomb shelter to continue living at all costs in the toxic afterworld as it does the last gasp of a person sealing the hatch forever. “Flood” sounds as Old Testament as the title suggests, The Flood destroying everything old so that something new can be built in its place. Something pure. But my favorite track is “No Passage” with its eerie Konami sunset synth lead, silhouettes of bombed out buildings visible in the background against the orange red of dusk, words scrolling over it telling us of the sacrifice of our adventure as the wind blows through our cloak, our crossbow slung over our shoulder with one arrow left, our pet wolf with electric eyes at our side as we walk into the burnt, uncertain future.

After spending two albums exploring the back and forth alleys and thoroughfares of Ivensville (must haves for all underground synth humanoids), Giftgarten, their third, is Pure Ground’s best, most atmospheric release to date, each track leading into the next the way a real album should like chapters of a novel, or segments of a lost anthology horror movie found in a forgotten corner of the fallout shelter. This is fantasy music in the best sense possible, bedroom headphones music designed to invoke visions and daydreams with its murky vocals that sound either wounded or like scratchy radio communications from some arctic base far away from first strike calling out for fellow survivors… or maybe warning them to stay away. The compositions and arrangements are tighter, more sophisticated than their previous efforts, that unmistakable low pinging bass sound from the bottom of the sea that’s come to define them throbs along as those snares that sound like acid being thrown on an old aluminum trash can smash through tracks like “Meager Arms of Sleep.”

Pure Ground, Giftgarten

Pure Ground are that rare sort of band, artists who evoke a theatrical and ominous sort of dystopia with fantasy authoritative flourishes without ever feeling dogmatic. It’s all atmosphere, all theater, rooted in some very real ideas; nightmare and daydream fuel. Their sound is staunchly, aggressively electronic. Gear based, it sounds weirdly wet, grimy, rusty. Visceral electronics. The “PG” monograms stitched into the shirts they wear on stage simultaneously suggest the symbols worn by futuristic submarine commanders as well as the symbol of some imaginary video store they may work at once civilization gets rebuilt after the war and humanity needs video stores again.

The apocalypse we once envisioned during The Cold War seems more and more unlikely. Environmental collapse, terrorism, epidemics of horrible new diseases seem more and more likely scenarios for extinction than a mass volley of two superpowers’ nuclear arsenals. The days of being afraid of one giant thing that will destroy everyone, everything, all at once seems like a far off, strangely sweet idea in a way. As The Internet fuels our minds with fantasies and illusions of eternal connectedness, as it separates us as much as it brings us together, the idea of any one reality being better or more relevant than another seems more and more ridiculous. Everything is real, nothing is real. Are we living in the apocalypse now, a place no filmmaker or science fiction writer ever imagined filled with limitless access, bottomless choices where few (if any) consequences for our insatiable consumption exist? Did the bomb drop in the form of The Internet? Did the world end in a mouse click, not a bang?

If so, Pure Ground might be the perfect band for our era. DIY electronics that insist if the world is going to end, it’ll end in clanging analog synths and ghoulish vocals, not a whimper.

The Terminator, 1984

Lawrence Pearce is an artist and electronic musician in Los Angeles. @novemura